A Note on Tariffs and Reciprocity

The Trump Tariff Formula is Not Just Wrong but a Direct Challenge to the Benefits of Foreign Trade

On April 2, the Trump administration unveiled its reciprocal tariff agenda, presenting a list of countries alongside two figures: the tariff rates these countries supposedly charge on U.S. exports, and the retaliatory tariffs the U.S. would impose in return (1/2 the previous value).

This came in addition to a proposed baseline tariff of 10% imposed across all imports, as well as various sector-specific tariffs. However, it quickly became apparent that the figures used in the reciprocal tariff plan bore little resemblance to actual tariff rates.

In reality, the "tariff charged" by each country wasn’t a real aggregate or estimate of tariffs at all. It was derived from a formula for the net export ratio with each partner country:

(Exportsᵢ – Importsᵢ) / Importsᵢ

—that is, how much more the U.S. exports to a country than it imports, expressed as a share of imports. Two additional terms were added in the denominator — one for price elasticity of import demand (set at 4) and one for import price passthrough (set at 0.25) — but since 4 × 0.25 = 1, they effectively cancel out and don’t change the result.

The problem? This formula doesn’t reflect tariffs independently. It contains but doesn’t practically measure how much a country taxes U.S. imports at the border, it simply reflects trade balances.

Trade balances are shaped by a wide range of factors beyond policy: comparative advantage, specialisation, and factor endowments — the very dynamics that drive mutually beneficial trade. Using this measure as a proxy for unfair trade practices mischaracterises the nature of the global exchange of goods and services and undermines the economic logic of trade itself.

A trade deficit doesn’t imply another country is cheating. If a country exports more to the U.S. than it imports, it could very well be the result of relative natural or structural advantages in producing certain goods. Comparative advantage is the principle that countries gain from trade by specialising in goods that they produce at relatively lower opportunity costs—even if one party is better at producing in absolute terms. The gains from trade do not necessarily arise from pure dominance in production but from differences in relative efficiency, giving up less to produce a good.

Thus we buy goods from countries that produce at a lower relative cost and both buyer and seller benefit. By using trade imbalances as a proxy for unfairness, the Trump tariff formula misdiagnosed the problem and undermines the very logic that makes trade beneficial. Rather than addressing barriers to international trade it captures trade’s greatest strength and makes it a political liability.

So if those weren’t real tariff rates, what do the actual tariffs look like?

Fortunately, we don’t have to guess. The World Trade Organization (WTO) maintains a comprehensive database of tariffs and non-tariff barriers imposed by its member countries. One key indicator is the WTO Most Favored Nation (MFN) applied average tariff rate, a straightforward, unweighted average of the tariffs a country applies to imports from other WTO members under standard, non-preferential trade terms. These are the observed rates charged at the border, reflecting each country’s actual trade policy rather than its trade balance, and when we compare them to the values reported by the White House, a very different picture of global trade emerges.

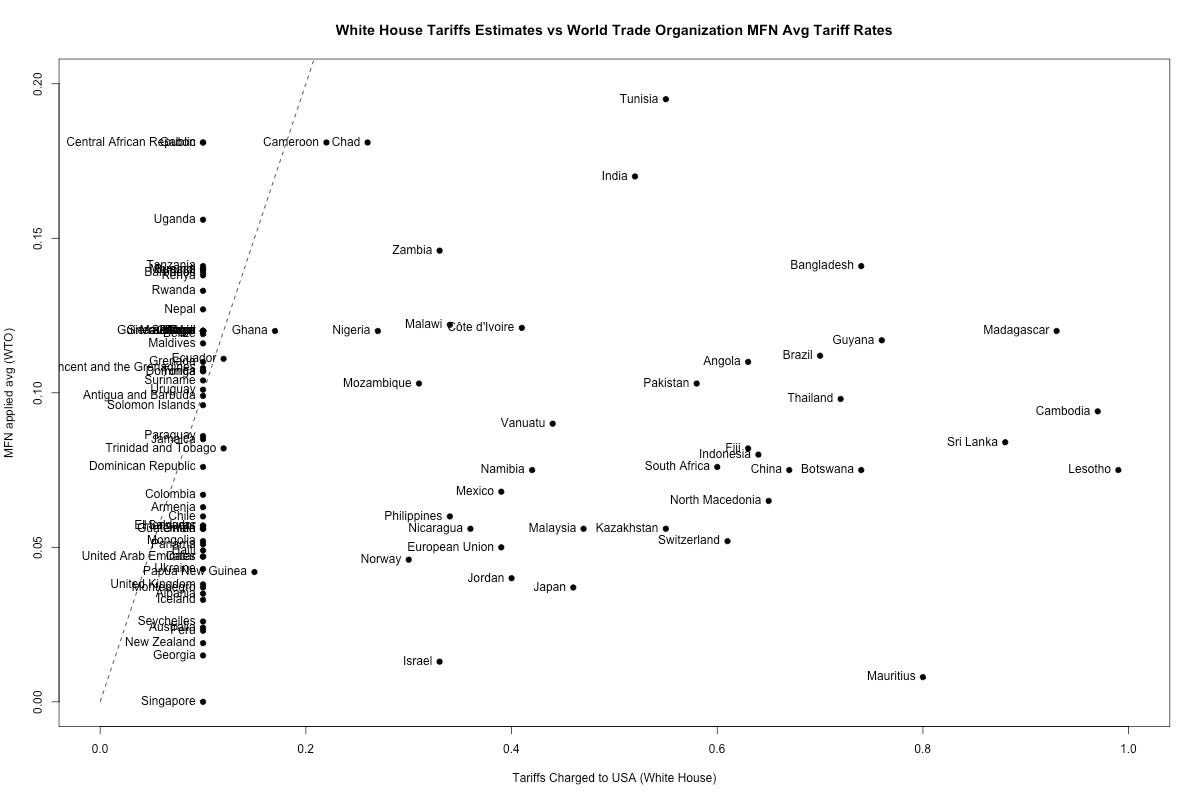

The chart above clearly illustrates the gap between political narrative and economic reality. On the X-axis are the Trump administration's "tariff estimates," derived not from WTO schedules or customs data, but from bilateral trade imbalances. On the Y-axis are the WTO-reported MFN applied average tariffs, representing what countries actually impose on U.S. goods exports. If the White House estimates were accurate, we would expect most countries to cluster near the dotted line, representing a 1:1 rate. Instead, we see a dramatic skew: the vast majority of countries lie well above the line, indicating that the administration's estimates consistently overstated how much the U.S. is being "charged," with many clustered above the arbitrary 10% mark.

This stark mismatch reveals that the trade deficit-based formula functions less as a measure of real-world protectionism and more as a tool for justifying tariff retaliation. By treating a trade imbalance as a stand-in for unfairness, the formula conveniently transforms fairly normal patterns of trade specialisation into evidence of exploitation. The result is a policy rationale that over-tariffs nearly every country including allies, major trading partners and low-income countries alike, while under-tariffing only a small handful, most of which already benefit from preferential access or have limited export capacity. This is illustrated clearly when shown on a country-by-country basis.

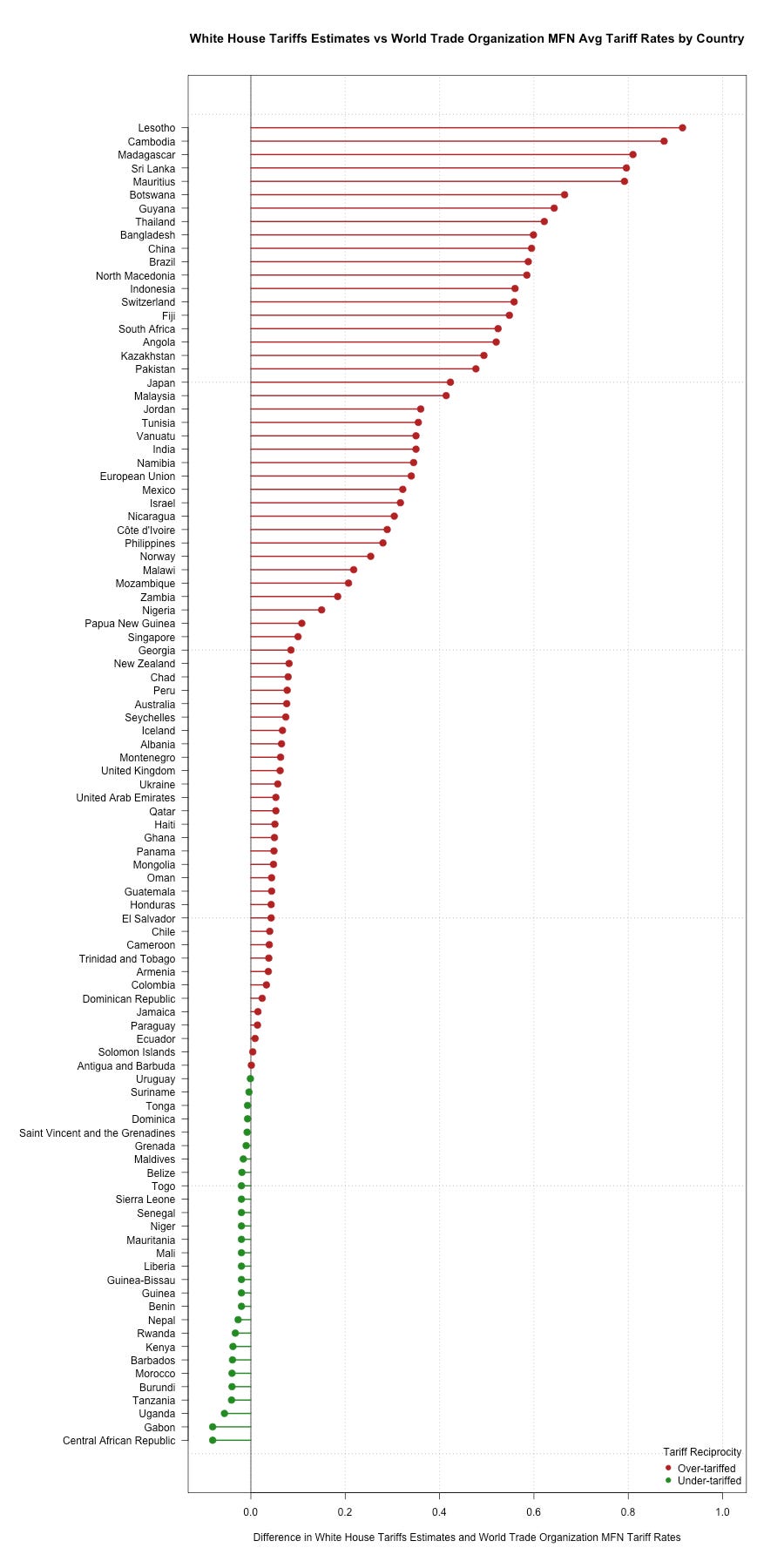

This chart expresses the same data in a slightly different form, providing a visual summary of the difference between the Trump administration’s estimated tariffs and the actual MFN applied average tariffs reported by the WTO country-by-country.

Many of the largest overestimations fall on low-income or small developing countries like Lesotho, Cambodia, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, among others. Somewhat ironically, the Trump administration’s formula ends up penalising the very countries the U.S. has chosen to support through trade preferences and programs like the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), which lowers or eliminates tariffs on exports from developing nations. Many of these countries specialise in low-cost manufacturing, particularly in textiles and apparel, sectors where the U.S. often runs trade deficits simply because it's no longer cost-effective to produce these goods domestically.

Major industrial economies like Germany, Japan, and South Korea frequently mentioned as competitors in Trump’s trade speeches are not extreme outliers in the actual WTO data. Their average tariffs are all relatively low. Even China, which remains a central target of Trump’s trade war and does have higher-than-average tariff rates is still subject to disproportionate retaliation.

This reinforces the idea that the Trump administration's reciprocal tariff policy was not grounded in real tariff data, but rather in misleading metrics derived to target trade balances. The overwhelming dominance of red lines where the White House overestimated the tariff charged on U.S. goods relative to the actual WTO rate is much lower, underscores how the administration systematically exaggerated the tariffs the U.S. faces abroad.

The Political Economy of Reciprocity

The specific country breakdown highlights a key contradiction: the reciprocal tariff agenda aimed to enforce "fairness," but in practice, it mischaracterises allies, marginalises partners, and misreads trade patterns. It didn’t reveal protectionism — it reflected the deeply flawed assumptions of zero-sum bilateral trade. And in doing so, it risked undermining real diplomatic and economic relationships. Rather than offering a coherent measure of reciprocity, this approach projects administration grievances onto the data.

At the heart of the Trump administration’s reciprocal tariff order was an appeal to fairness. The idea was simple and intuitively compelling: if other countries are charging high tariffs on American goods, the U.S. should respond in kind until said barriers were removed. Rhetorically, this positioned the administration as simply demanding a level economic playing field. But it’s clear in practice, the policy's foundation was not built on actual tariff data or legal trade commitments. Instead, it relied on a misleading formula based on trade balances, not border taxes. This not only distorted the concept of fairness but defeated the very logic of reciprocity the policy was meant to uphold.

This approach is best summarised in the following quote provided in the reciprocal tariff calculation report: “If trade deficits are persistent because of tariff and non-tariff policies and fundamentals, then the tariff rate consistent with offsetting these policies and fundamentals is reciprocal and fair.” The explicit policy goal is to eliminate any trade deficit regardless of actual barriers.

Far from restoring fairness, the policy obscures it — recasting the benefits of specialisation as political offences, and offering tariff escalation not as a strategic tool, but as a form of symbolic punishment that will ultimately blowback on US economic interests.

You can read the full world tariff profiles report for 2024 from the WTO here, and access the executive order and reciprocal tariff calculations at the respective links.